General Contractor Contract: The Ultimate Guide for USA and Australian Builders

Ask any builder with a few years in the field, and problems don’t usually start on the job site. They start before the job begins, when expectations aren’t written down clearly. A solid general contractor contract helps you avoid all of that. It draws the line between what’s been agreed on and what hasn’t.

In this guide, we’re taking a practical look at how these contracts work, what they should cover, and how they’re used in real-world construction across the US and Australia. If you’re managing crews, working with subs, and wondering how to handle general contractor markup, this is the foundation you can’t skip.

Table of Contents

- General Contractor Contract Explained

- When Is a General Contractor Contract Used?

- 7 Key Elements of a General Contractor Contract

- General Contractor Contract Standards in the USA

- General Contractor Contract Standards in Australia

- 4 Tips for Reviewing or Drafting a General Contractor Contract

General Contractor Contract Explained

Before anything gets built, there’s got to be an agreement. Not just a handshake, or a discussion over coffee, but a written contract that shows what the job actually involves. A general contractor contract puts expectations on paper, so there’s no confusion once the crew starts. When things shift as they always do, the contract answers the hard questions.

- What was agreed on?

- What happens now?

- Who takes responsibility?

It’s protection for both sides and the only real plan B when problems show up.

Who Uses It and in What Situations?

Contractor contracts show up wherever things get layered with multiple trades, moving deadlines, and high expectations. That means:

- Custom home builders taking full control of a site

- Remodeling crews handling big additions

- Developers bringing in GCs for larger builds

- Commercial projects where lots of subcontractors come in and out

If the project’s got more than one vendor, a stack of materials, and a timeline with moving parts, you’ll need a formal agreement. Otherwise, you’re risking your job to run off track.

Contractual Relationships It Defines

At the core is the deal between the builder and the client, usually the owner or developer. A contract spells out the work, the money, and what success looks like.

After that, the builder hires subcontractors and vendors to carry out the plan. Each of those players connects back to the original document. So, when something breaks down, it’s the main agreement that helps sort out who’s on the hook.

When Is a General Contractor Contract Used?

A general contractor contract comes into play when a builder takes full responsibility for managing a construction project, coordinating trades, materials, timelines, and client expectations. It’s not reserved for large commercial jobs. Even smaller builds require one when multiple trades are involved or if the scope, timing, and payments need formal control.

These contracts are typically used when:

- The project includes several subcontractors or vendors

- Work is delivered in defined phases, and there are many materials, schedules, and client approvals to be tracked

- Regulatory steps, like inspections or permits, are involved

7 Key Elements of a General Contractor Contract

A good contract shapes how the job unfolds on the ground. It can also protect you in court, when things go out of control.

From who’s doing what to how changes are handled, the structure you agree on becomes the backbone of the entire build. If these details aren’t nailed down early, they’ll come back to bite you later. Here’s what matters most.

Scope of Work

Start here. This part tells everyone what the builder is responsible for delivering. It should include:

- Specific trades and tasks involved in the build (framing, cladding, concrete, roofing, etc).

- Architectural drawings and engineering plans the job will follow, including revision numbers and version dates.

- Exclusions that the builder will not provide (e.g., landscaping, demolition, utility fees).

- Client-provided items, if any, such as appliances, light fixtures, or specialty finishes.

Vague descriptions cause problems. “Interior remodel” might sound clear enough, but it leaves too much open. Point to the plans and list the tasks in detail. When a client asks for something unexpected, this is the page you go back to.

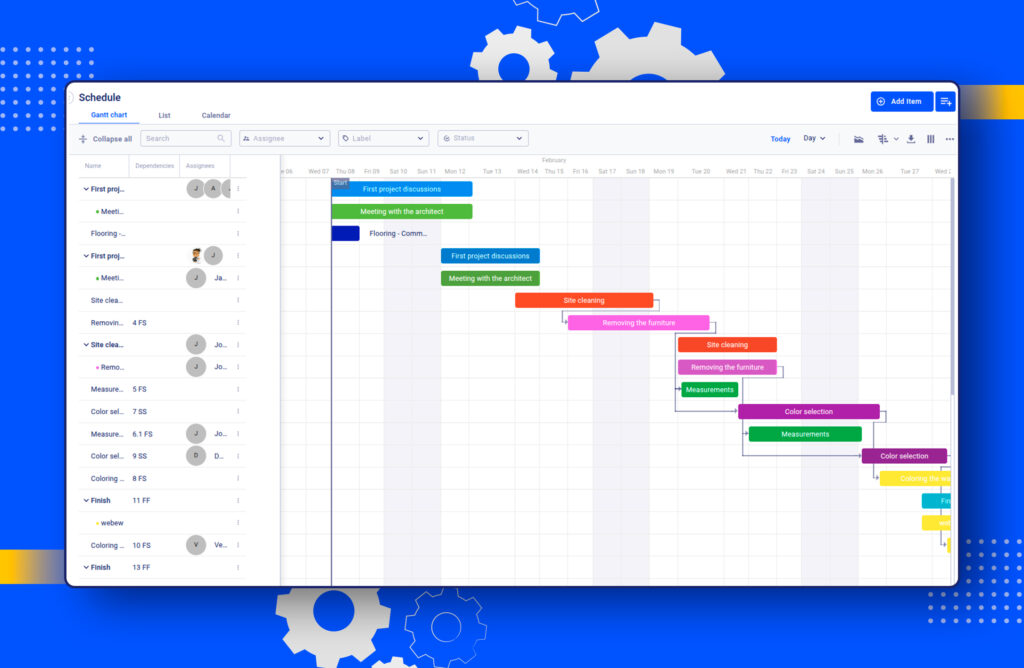

Timeline and Schedule

Every project needs dates, but a finish date isn’t enough. You need structure.

- Planned start and completion dates, with enough buffer period to account for unexpected issues.

- Breakdown of key phases, such as slab pour, frame inspection, cladding, etc.

- Deadlines tied to external factors, like permit approvals, design sign-offs, or client decisions.

- Milestone approvals and windows for inspections, so all the involved teams know when to pause, notify, and move forward.

Some contracts ask for daily reports. Others offer bonuses for early wrap-ups. Regardless, dates should be tied to real progress, not just calendar boxes. And if the weather hits or a client stalls a decision, that needs to be accounted for, too.

Project Cost and Payment Terms

This is where it gets serious. The next section is all about the numbers and how they flow.

- Pricing method, whether it’s fixed price, cost-plus, or per-unit.

- Billing format, whether it’s draws schedules, milestone-based invoicing, or monthly progress claims tied to the actual work.

- Retainage terms (usually between 5-10%) and it’s release period.

- Conditions for withholding or delaying payments, such as incomplete work, failed inspections, or unapproved variations.

In the U.S., especially on commercial sites, builders often use the AIA system G702/G703 with a schedule of values.

In Australia, it’s more common to include provisional sums or prime cost items, especially in AS 4000 contracts. The structure varies, but the goal’s the same: everyone knows when and how the money moves.

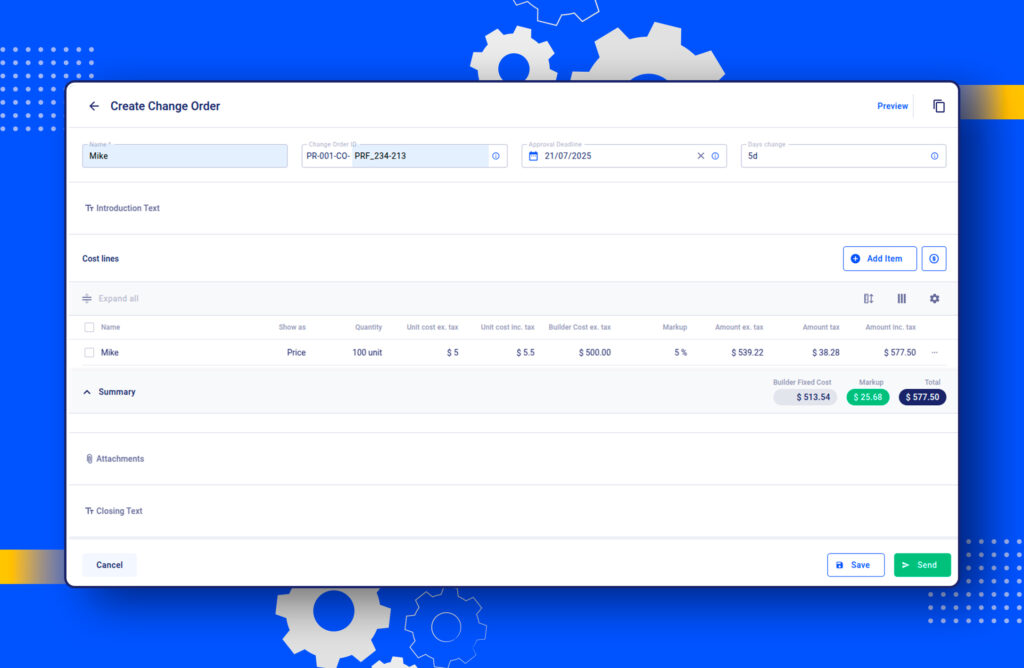

Change Orders

There’s no such thing as a project with zero changes. This clause manages the change orders that come, whether they are expected or not, meaning it should define:

- How a change order is submitted, include the initiator, how it’s documented, and when it’s allowed.

- What must be included in the change order: scope of work, pricing breakdown, and any time extensions.

- Stakeholders who need to approve the change (builder, client, architect) and in what form.

- Cutoff points for accepting changes, such as after framing or before ordering materials.

In Australia, these are called variations, and the AS 4000 and AS 2124 contracts spell out how they’re handled.

Insurance and Liability

Risk lives on every site. This section makes sure everyone knows who’s responsible when things go wrong. A solid contractor contract should cover:

- Required policies: general liability, builder’s risk, workers’ compensation, and any project-specific add-ons.

- Which party provides what, whether it’s the builder, subcontractor, or the client.

- What happens if something gets damaged or someone gets hurt.

- Whether the client must be listed as an additional insured, which is common on larger projects and commercial builds.

Warranties

Most builders include a warranty in the contract. It usually covers labor and materials. But not everything, and not forever. For this reason, the warranty section has to be clear. It should cover:

- Warranty duration that typically lasts from 12 to 24 months for workmanship and material, with longer coverage on structural elements if required by the law.

- What’s included (and what’s not), like framing, finishes, or mechanicals.

- Manufacturer warranties, including appliances, HVAC systems, etc.

- Steps the client must take to make a claim, including timelines, proof of issue, and acceptable formats.

Sometimes a product comes with its manufacturer’s warranty. Say, a water heater or a range hood. Those often transfer to the client directly. That’s fine, but it needs to be spelled out. What matters here is that everyone knows who’s on the charge and for how long.

Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

Even with a great contract, problems can still come up. This part of the builder agreement explains how to deal with them if they do.

- How disputes are raised, including required notice, written summaries, or who needs to be present for a resolution meeting.

- First step for resolution, including direct negotiations, mediations, and neutral third parties.

- Actions if there’s no agreement, and when it escalates to binding arbitration or litigation.

- Whether the project continues during a dispute or if work pauses while the issue is resolved.

It sounds straightforward, but this part often gets ignored until it’s too late. If the language is vague or missing, even a small issue can bring the project to a standstill. You don’t want to be arguing about how to argue. Get this nailed down upfront.

Subcontractor and Supplier Agreements

Builders take the lead on hiring and managing trades, with multiple risks often showing up in the process. Expectations should be written down clearly on paper to define aspects like:

- The team members who are responsible for picking the subcontractors and overseeing their work.

- Performance expectations for the third-party teams, including timelines and their adherence to job site rules.

- Who’s liable if a sub causes delays or defects, especially when rework or penalties are involved.

One other thing general contractor contracts include is what’s called flow-down clauses. These push the main contract’s rules down to the subs. That way, if the builder agreed to certain safety standards, timelines, or deliverables, the subs are held to the same. It keeps the whole job aligned. And it protects the builder when someone else messes up.

General Contractor Contract Standards in the USA

If you’ve built in more than one state, you already know that these contracts don’t play by one national rulebook. Payment timing, lien protections, and dispute procedures shift depending on where the job is. Similarly, most builders don’t rely on homegrown documents. They lean on standards that have been tested across states, projects, and legal systems.

In the U.S., the most widely used standard-form contracts come from the American Institute of Architects (AIA). And while the name might suggest these documents are for design teams only, that’s not how the industry treats them. Builders, engineers, architects, and owners use them to keep large projects moving with fewer legal surprises.

AIA isn’t a regulatory body, but a professional organization that’s spent decades refining contract templates for construction. These documents set the required expectations, define responsibilities, and lay out what happens when plans change or problems hit.

If you’re building anything with engineers involved, staged funding, or more than one subcontractor, odds are, AIA documents have every template to cover the workflow.

AIA Contract Documents: The Gold Standard

You don’t need to use the full library. Most general contractors stick to a few core agreements:

- A101: Owner/Builder Agreement (Lump Sum)

This is the baseline contract when the builder is working for a fixed price. Covers scope, payment terms, and risk. - A201: General Conditions

Governs job site rules, change orders, delays, and dispute handling. Usually paired with A101 to form a full contract. - B101: Owner/Architect Agreement

Even though it’s between the client and designer, it often shapes your scope, especially when plans are evolving mid-job.

Why Builders Use Them

They reduce guesswork. Everyone sees the same version of responsibility. It’s also beneficial as you are not starting from scratch, as all the terms are court-tested and legally familiar to other builders, banks, and legal entities.

On smaller residential jobs, some builders skip AIA docs because of the perceived overhead. But that can be a mistake. The templates are modular. You can adjust them, remove clauses, add schedules, and clarify what’s included. And once your team’s used to the format, they save more time than they cost.

General Contractor Contract Standards in Australia

Australian builders work in a legal environment shaped by common law and layered contract obligations. While each state and territory has its construction codes and case precedents, contract law remains largely consistent nationwide. What matters is how well the contract reflects the project’s intent and how clearly responsibilities are assigned.

In practice, most large-scale builds across Australia rely on standard form contracts. These aren’t created by builders or clients from scratch. They’re drafted by institutions like Standards Australia, reviewed by legal professionals, and widely adopted across government, civil, and commercial sectors.

Whether you’re pricing a tender for a public school or managing a private D&C job, odds are your contract terms are built around one of these.

AS 4000 and AS 2124: Most Widely Used Standards

These two remain the cornerstone of Australian contract practice. While each serves a different purpose, they cover similar risks, just with a different structure.

AS 4000: Construct-Only Contract

- Used when the client provides full design documentation upfront

- Puts responsibility for construction (not design) on the builder

- Includes clear rules for time extensions, variations, delays, and liquidated damages

- Widely used in civil, commercial, and public infrastructure work

Builders like AS 4000 because it’s relatively straightforward. It includes built-in procedures for things like progress claims, site instructions, and dispute resolution, so there’s less need for extra clauses.

AS 2124: Traditional Contract (Older Standard)

- Still used by many government departments and major asset owners

- Slightly more complex in wording and structure

- Requires more legal review when customized

- Often modified with annexures or special conditions

AS 2124 has been around longer and has more legal history behind it. That’s part of its strength and part of its complexity. Many firms still use it because their consultants are familiar with its language and risk allocation patterns.

In both contracts, variations (the Australian term for change orders) are strictly documented. Time bars, written approvals, and formal notices are the norm; verbal agreements rarely hold up.

Other Australian Standard Contracts

Beyond AS 4000 and AS 2124, other contract forms fill different roles depending on the delivery method:

- AS 4902: Design & Construct (D&C)

Used when the builder is responsible for both design and delivery. Popular in commercial and mixed-use jobs where the client wants a single point of accountability. - AS 4912: Construction Management

Suitable for projects with multiple trade packages. The builder acts as a manager, not a contractor, and the client holds direct contracts with each trade. - AS 4300: Earlier D&C Format

Largely replaced by AS 4902, but still in use on older frameworks or with conservative consultants. - Government and Defence Contracts

Departments like the NSW Government or Department of Defence often issue their own modified versions of these standards. They follow similar principles but include specific compliance and security terms.

Across all formats, contract language is detailed and legally strict.

Builders operating under these standards need tight documentation, reliable approvals, and consistent records of instructions and variations. There’s little room for informal changes once the contract is signed.

4 Tips for Reviewing or Drafting a General Contractor Contract

#1 Always consult a construction lawyer

Don’t guess. Don’t copy what worked last time. Contracts, especially on unfamiliar projects or public tenders, deserve a proper legal check. You want someone who deals with construction law, not just someone good with agreements in general. A short consult can save months of headaches later.

#2 Ensure clarity of scope and payment structure

Loose terms like “full remodel” or “payment due on completion” leave too much room for argument. Break things down: what’s included, what isn’t, and what has to be finished before a payment goes out. Tie money to progress instead of simple dates, and be clear about what documents need to be submitted with each invoice.

#3 Define a process for changes and delays

This is where most jobs hit friction. Change orders or variations need rules. Who can approve them? When? What counts as valid? Same with delays. Time extensions should follow a certain process, such as a written notice, an approval window, and documentation.

#4 Confirm regulatory compliance

Does the contract cover licenses, insurance certificates, and safety requirements? Who’s responsible for pulling permits or notifying the council? Who tracks inspection deadlines? If these aren’t laid out clearly and backed by deadlines and documentation, it’s easy for tasks to slip. If the builder owns it, it needs to be in writing.

1. What is a general contractor contract, and why do I need one?

It’s the deal, but in written form. The builder agrees to deliver a job. The client agrees to pay. It covers scope, deadlines, payment rules, and who’s on the hook if something goes off track. Without one, you’re working off memory, and that won’t hold up if there’s a problem.

2. What details should be included in a GC contract?

The more specific, the better. List what’s being done, which materials are included, and anything that’s not part of the deal. A complete general contractor contract should cover more than just price and dates. At a minimum, it should clearly outline:

- The scope of work

- The project timelines with key milestones and allowed delays

- The pricing structure and how payments should be handled

- Change order procedures with written approval requirements

- Rules for subcontractors and vendors

- Dispute resolution terms for mediation, arbitration, and jurisdictional disputes

- Any warranty terms for labor or materials

3. What is the best contract for general contractors?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. The best GC contract depends on multiple factors, with the most important ones being where you’re building and what kind of project you’re talking about. In the U.S., many builders lean on AIA standard contracts, especially for commercial or multi-phase jobs. In Australia, it’s common to use AS 4000 or AS 2124, depending on the delivery method.

4. What makes a contract invalid?

A contract can be considered invalid if it’s missing any of its key elements: mutual consent, lawful purpose, clear terms and scopes, or the legal capacity of the parties involved. It can also be voided if it’s signed under duress or goes against local laws and licensing requirements. Without these basics, the agreement may not be enforceable in court.